Halfway through 2013, and the FCC’s pace of unlicensed broadcast enforcement shows no real change from 2012: 106 enforcement actions in all, targeting more than three dozen stations, with the majority of this activity wholly administrative in nature. Pirate stations who appear on the FCC’s radar can now expect a warning letter to arrive via certified mail 1-6 weeks after an initial visit. Ignore those, and the agency may start asking for money.

To date, the FCC has handed out $60,000 in Notices of Apparent Liability and $125,000 in actual forfeitures. However, not all of these penalties are new: in February, the FCC socked Whisler Fleurinor with a $25,000 fine for unlicensed operation in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. This is actually Fleurinor’s second go-round – he was first busted in 2010 and given a $20,000 forfeiture in 2011, which was later reduced to $500. It’s much the same story for Gary Feldman, who was first busted in 2004 for pirate broadcasting in Miami. He was caught again last year and fined $25,000 this year. Moreno’s 2004 forfeiture ($10,000) was never paid.

To date, the FCC has handed out $60,000 in Notices of Apparent Liability and $125,000 in actual forfeitures. However, not all of these penalties are new: in February, the FCC socked Whisler Fleurinor with a $25,000 fine for unlicensed operation in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. This is actually Fleurinor’s second go-round – he was first busted in 2010 and given a $20,000 forfeiture in 2011, which was later reduced to $500. It’s much the same story for Gary Feldman, who was first busted in 2004 for pirate broadcasting in Miami. He was caught again last year and fined $25,000 this year. Moreno’s 2004 forfeiture ($10,000) was never paid.

Several other forfeitures this year involve reductions on previous penalties. For example, Bernabe Moreno (NJ) saw a 2011 fine reduced from $10,000 to $1,000; Michael Gregory (FL) whittled a $10,000 forfeiture issued last year down to $750 this year; and Recardo Mill word (NY) caught a $16,000 break on appeal of a 2011 NAL.

Despite the FCC’s best efforts, pirate radio remains a coast-to-coast phenomenon, with enforcement actions reported so far this year in 18 states and the District of Columbia. That said, the FCC is definitely doing more legwork on some cases and seems to be working more closely with local law enforcement agencies.

In the process of tagging Fabrice Polynice with a $25,000 fine for unlicensed broadcasting in Miami, the FCC tracked the movement of the station to three different locations over the course of six months. Elsewhere in Miami, the FCC did some IP tracing to tie Bernard Veargis to a pirate station; that setup was dirty, throwing a spur onto one of Miami International Airport’s departure frequencies, which made shutting him down a high priority. Similar interference was reported at Boston’s Logan International Airport, which led to a March raid on a station in Brockton, Massachusetts. (The FCC had known about this station since 2010.)

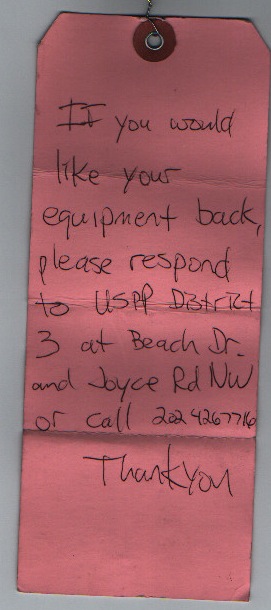

Although raids and seizures remain more the exception than rule, there’ve already been five this year. Victims include WSQT Direct Action Radio in Washington, D.C., an insurgent voice on the FM dial of the nation’s capital for more than six years. The U.S. Park Police confiscated the station’s remote transmitter setup in April. Fortunately, WSQT’s operator remains at large and is already

Although raids and seizures remain more the exception than rule, there’ve already been five this year. Victims include WSQT Direct Action Radio in Washington, D.C., an insurgent voice on the FM dial of the nation’s capital for more than six years. The U.S. Park Police confiscated the station’s remote transmitter setup in April. Fortunately, WSQT’s operator remains at large and is already ![]() constructing replacement gear.

constructing replacement gear.

Others have not been so lucky. Two men were arrested last month in Summerfield, Florida for running commercial station "Fuego 97" from a trailer-home; both have been charged under Florida’s own anti-pirate law, which makes unlicensed broadcasting a third-class felony. According to news reports, an engineer from Clear Channel did the hunting and then handed the case off to the cops and FCC.

Two men were also arrested in Brooklyn, New York last month for pirate broadcasting – a class A misdemeanor according to a state statute enacted last year. Several NYC stations complained that an illicit competitor was "infringing on their business," and NYPD detectives went so far as to buy commercial time from the broadcaster. But when they raided his station in April, they actually found two stations in operation there. These arrests are believed to be the first ever under New York’s anti-pirate law. (Florida, New Jersey, and New York are the only states where pirate radio has been locally criminalized.)

Lest this activity makes one think that it’s really dangerous to be a radio pirate, keep in mind that I once pulled in 11 unlicensed FM stations from my home in Brooklyn earlier this spring. Meanwhile, in Reno, this news report makes it sound like the Nevada Broadcasters Association is negotiating with a religious pirate to shut down. And in Boston, a long-time sportscaster and talk show host has signed up to do a show on Touch FM – an unlicensed station so out in the open that its founder is running for mayor.

Looking at pirate radio enforcement efforts is an indirect way to measure actual pirate radio activity. But even so, it’s clear that the scene is as vibrant as ever.

Skip to content